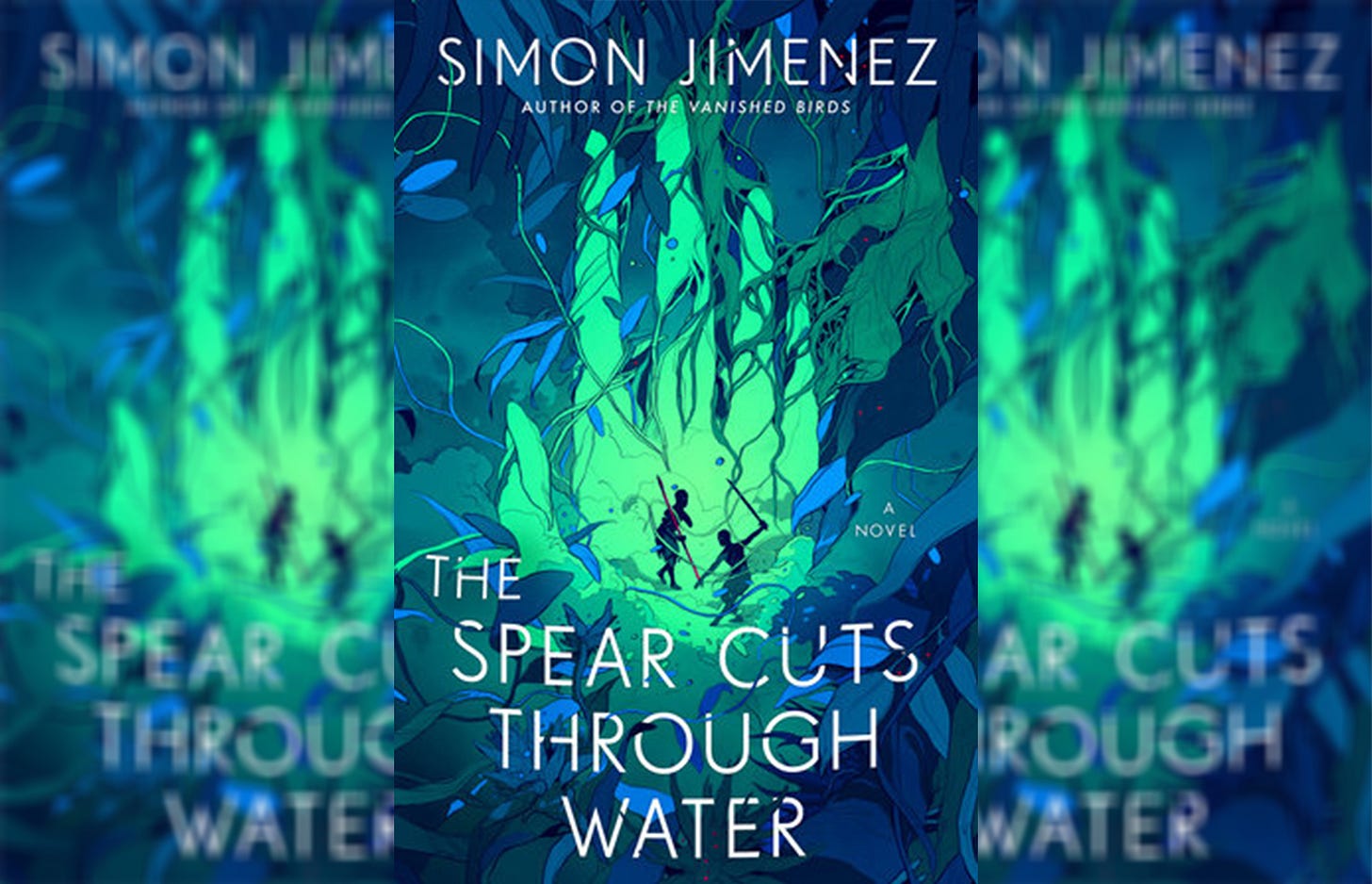

The Spear Cuts Through Water is the best overlooked book of the last year

It's got fans. Not in its publisher's promotions department, however.

There are paragraphs, maybe even whole pages, of The Spear Cuts Through Water that you could show to a longtime fantasy fan, and they would say “Hmm, yes, well written, fun stuff. But what’s so different about it?”

But start at the beginning, and you can’t mistake what Simon Jimenez has done for a standard fantasy adventure novel. You can find one within it, sure, but it’s wrapped up in layers of the kind of literary structure you just don’t find in most genre novels. Or most novels, period.

The Spear Cuts Through Water is, in part, the tale of Jun and Keema. (“This is a love story to the blade-dented bone,” we’re reminded a few times, even as it takes most of the book to get there.) Jun is the grandson of the recently-violently-deceased emperor, and a now-repentant member of his father’s war band. Keema, by contrast, is no one in particular – a one-armed and insignificant soldier in a small outpost run by a drunken officer. They’re going to do the quest thing. Jun has freed the dying Moon Goddess, long the prisoner/progenitor of the imperial line, and is taking her to her true love, the sea. Keema has to carry a family-heirloom spear to a coastal port and give it to a particular soldier, the dying wish of his commander. Along the way, there will be troubles with the Emperor’s sons, the Three Terrors, and with various other nobles, rebels, spirits, monkeys, sentient telepathic tortoises, and also the sea is angry and that’s real bad news…

And this could have been the whole book! It would have been a well-reviewed book, a book notable for being just a little bit outside of the standard quest narrative box, for mingling fantasy structures and what feel more like folkloric elements. It might have sold like crackerjack.

But Jimenez doesn’t just give you this story. He gives you more.

Because The Spear Cuts Through Water does not begin with Jun and Keema and the cruel emperor and his cruel sons and the dying, ancient goddess.

It begins with you.

It begins in second person, with a child listening to his grandmother’s stories, in a house with too many brothers and a distant father, in a country with radio serials and cars, on the verge of war with an unspecified enemy.

And some of the stories your grandmother tells touch on the spear, the family heirloom that came from the Old Country, and has hung above the mantelpiece for generations, and sometimes, she talks about the moon goddess, about her love for the sea, and about their child, who built a theatre that people visit in their dreams, and never remember afterwards.

That theatre links these two narratives. Our nameless protagonist goes to sleep one night, and carrying the family’s spear, visits this grand theatre, and the child of the moon and the sea and a host of spectral dancers take to the stage, and they act out a grand drama from the old country – the story of Jun and Keema and the dying goddess.

This is a wild structure for a book published as straight-up fantasy. And the thing I cannot get over is how beautifully structured it is, how perfectly balanced. This is not simply a nested narrative, like Russian dolls, with two outer shells of narrative containing the story of Jun and Keema. No, we shift back and forth multiple times between our fantasy quest and the world of the narrator. We see his (probably a he?) shifting fortunes, his father’s disappearance, his grandmother’s death, his life leading up to the night he dreams himself into the theatre. We drift in and out of the core narrative, reminded every now and again that, somehow, this story is being presented as a dance, through music and song.

And it is goddamn seamless. It should not work nearly as well as it does.

And within that core narrative, which has room for swashbuckling fights and leaping bears and explosions, there are grace notes that you wouldn’t find in a typical story. The most notable is the presence of italicized text at regular intervals, giving us the thoughts of dozens of people whom the main narrative touches – peasants, guards, killers, the luckless dead – and these impressions form a kind of Greek chorus, commenting on the narrative, on how its events affected them.

It’s definitely one of the best books I’ve read in the last year – fun, engaging, beautifully crafted, moving. It works on pretty much ever level. You should read it. Even if you don’t like it, you won’t find it much like your typical SFF novel.

And now that we’re done praising the novel, let us talk about how the science fiction and fantasy promotional system let it down so badly.

The Spear Cuts Through Water was published, by Del Rey, on Aug. 30, 2022. I had not heard about it prior to its release, nor had I ever heard of Jimenez’s first novel, The Vanished Birds. Despite being immersed in SFF Twitter, I didn’t hear about it at all until October, when author J.T. Greathouse recommended it to me pretty fervently in a Twitter discussion of books featuring experimental and dazzling prose.

He thought it was pretty good:

And I made a note to check it out, and I read it, and by the time I was halfway through, I was tweeting like that too.

But where the hell was the promo?

There were good reviews. Kirkus put the book on its best of 2022 list for science fiction and fantasy. Locus loved it to bits.

And there’ve been other reviews, most positive, many gushing, but that’s about it. Tor.com had a single article about it, focused on the book’s unique and lovely map (another clever subversion of the standard fantasy novel template).

(Jimenez himself wisely seems to have no social media presence. Bad for promo, good for living a psychologically health life.)

I don’t want to set books against one another, but it’s impossible not to think about the tsunami of publicity that attends some books in the field, while Spear got squat. Gideon the Ninth comes immediately to mind, with its dominance of discourse for weeks, its reviews in places like Vox and NPR, giving it a vastly wider potential audience than the niche audience usually targeted for new SFF releases.1

I can’t say what happened with Spear. Probably the same thing that happened with a dozen other books that are also good to great, and also doing interesting things with structure and prose and ideas, and which I haven’t heard of at all. The publisher looked at their calendar, looked at their stingy promotions budget, and put the big money on something else. And left The Spear Cuts Through Water to fend for itself.

So how is it doing?

I’ve seen a number of folks with high numbers of Twitter followers recommending it, which helps, as will the Kirkus list. But it did not make the Goodreads Choice awards top-20. This is a crime, folks.

I’ve already said enough about how discoverability is broken around these parts, so just… I dunno. Go read the book. It’s good. It’s beautiful, it’s fun, it’s not like whatever you read previous to it.

And tell your damn friends. Del Rey won’t.

Recent reading

I’ve most recently read Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, (also good) and I’m nearing the end of a 2017 cyberpunk novel called Void Star – yet another book that passed me by, despite it being Very Much My Kind of Thing, and about which I’ll have more to say in a future newsletter.

I am not saying Gideon the Ninth deserved less promo. I’m saying The Spear Cuts Through Water deserved at least some measurable fraction of that level of attention.

Absolutely agree that this is one of the most original fantasy books I've read. Beautiful prose, stunning structure. I did see it on display recently at my local Barnes & Noble, right in front on the New and Top Fiction shelf. And I'll be promoting it soon in a fantasy book giveaway in a few weeks, because more people should read it.

Just wanted to say this review has been lodged in my head since I read it, and so, since my fun money budget is refreshed with the start of a new month, I'm heading out to pick up this book today.